[The following article was originally given as a presentation at an interfaith symposium, Fasting in Religion, on June 22nd, 2017, sponsored by the Ahmadiyya Muslim Jama’at of Richmond Hill, Ontario-Canada. There were three presenters, a rabbi for the Jewish understanding of fasting, an imam for the Muslim understanding, and myself, presenting for fasting in the Christian context. The presentations were then followed by a Q & A with the audience.]

The Bible informs us that there are certain practices, such as prayer, fasting, celebration, solitude with God as well as others, that we can undertake in cooperation with God’s grace, to raise the level of our lives toward godliness. These activities have often been referred to as spiritual disciplines, disciplines of mind and body purposefully undertaken to bring our personality and entire being into effective cooperation with the divine order.

When practiced, these disciplines enable us more and more to live in a power that is, strictly speaking, beyond us, derived from the spiritual realm itself, as we “offer ourselves to God as those who have been brought from death to life; and we offer every part of ourselves to him as an instrument of righteousness,” as Paul wrote in Romans 6. The necessity for such disciplines comes from the very nature of the self as created in the image of God. Once the individual has, through divine initiative, become alive to God and his Kingdom, the extent of the integration of his or her total being into that Kingdom will significantly depend upon the individual’s initiative.

When practiced, these disciplines enable us more and more to live in a power that is, strictly speaking, beyond us, derived from the spiritual realm itself, as we “offer ourselves to God as those who have been brought from death to life; and we offer every part of ourselves to him as an instrument of righteousness,” as Paul wrote in Romans 6. The necessity for such disciplines comes from the very nature of the self as created in the image of God. Once the individual has, through divine initiative, become alive to God and his Kingdom, the extent of the integration of his or her total being into that Kingdom will significantly depend upon the individual’s initiative.

The late Christian philosopher, Dallas Willard defined the spiritual disciplines as:

I will now focus on one of the spiritual disciplines within the Christian context, which is our subject for this evening, that of fasting. In doing so, I will briefly address three different aspects of fasting within the Christian worldview and their biblical context.

1. First, I will address very briefly the historical and biblical context;

2. Second, I will explain fasting as a spiritual discipline, which includes fasting in anticipation of ministry or miracles;

3. And third, I will address fasting as a transformational tool that results in compassionate service to others.

Historical Context

From the earliest days of the church, Christians have practiced fasting. Early Christians imitated Old Testament biblical characters that fasted, and sought to follow Jesus’ instructions about fasting in their lives.

Within the Christian context, fasting was never perceived as a sign of righteousness in itself. Early followers of Christ didn’t fast out of a sense of obligation, but in a desire to seek the Lord’s presence and out of necessity for the ministry of the gospel. Such discipline is encouraged as the Lord does his work through his people. However, the act itself did not have the kind of formalized or ritualized meanings it occasionally had for contemporary Judaism.

As William Thrasher so aptly put it,

Early church leaders such as Basil and Augustine wrote about the spiritual and physical benefits of fasting, urging their parishioners to practice discipline of the flesh. Regardless of abuses of fasting that later occurred within medieval monasticism and church formalism, the Protestant Reformers unanimously affirmed that fasting could find a proper role in Christian practice, and their followers sought ways to implement these ideals.

After the Reformation, the Church of England sought to balance fasting traditions with the Protestant emphasis on a free conscience. John Wesley, the founder of the Methodist Church, was the epitome of practicing such a balance, and he promoted fasting in both private and churchly devotion. Although fasting seems to have somewhat declined in the modern era of Christianity, the Spiritual Disciplines movement over the last several decades, has called Christians to renew a practice that has biblical warrant and thorough support from every wing of Christian tradition.

A prime example of contemporary fasting is the 40 day season of Lent, directly preceding the celebration of Jesus’ resurrection on Easter, which places a particular emphasis on fasting and was spoken of by the early church fathers such as Irenaeus and Athanasius. For many Christians, Lent is a time of ‘profound reorientation’, a time to imitate Christ and participate in his life in concrete ways. Lent commemorates Christ’s 40-day fast in the wilderness, and for many Christians, it is a spiritual journey whereby they identify with Christ, hoping to become more like him by looking within themselves, to examine their hearts and surrender themselves to Christ. It is also a time to look to others, to see how we, as Christians, might serve and lay down our lives for others as Christ has done for us. A recent Barna poll has shown that around 90% of Christians fast within the season of Lent, even fasting technology for a time.

Contemporary interest and emphasis in fasting has been highlighted in the work of the Quaker theologian, Richard Foster, in his 1978 book, Celebration of Discipline, in which he reported that his research could not turn up a single book published on the subject of fasting from 1861 to 1954, however, over the last several decades a volume of books has been published on the subject such as Shaping History Through Prayer and Fasting, by Derek Prince; Fasting: A Neglected Discipline, by David R Smith; God’s Chosen Fast, by Arthur Wallis, hence the sense of a ‘revival of emphasis’ if you will, on fasting within Christianity.

Biblical Context

While the Christian faith extols and emulates examples of biblical fasting recorded in the Old Testament, the primary focus of Christian fasting is centered on the person and work of Jesus Christ. This is due to the fact that central New Testament passages related to fasting specifically present this practice as a means for highlighting Christ and his messianic work.

Jesus’ ministry begins with two events—His baptism by John the Baptist, and His time of fasting and temptation for 40 days in the wilderness. Unlike Adam, the first man created from the dust, Christ endures temptations in the inverse of the ideal conditions of paradise. Satan attempts to cause Christ to fail even as the first Adam had failed, and in both cases in connection with food consumption. In overcoming these temptations and resisting Satan, he brings humanity at its weakest into complete submission to the will of God, showing that humanity can be united to divinity. As such, fasting is used both as a means to prepare Jesus for his messianic ministry, and to identify him as such in that role.

However, Satan’s attempt to repeat history failed when Jesus was presented with the same temptation:

Considering Jesus’ circumstances, it would seem that He was at a great disadvantage, humanly speaking, when confronted by the tempter, in comparison to the situation of Adam and Eve. Adam and Eve were in paradise, enjoying the fullness of God’s created provision, with the freedom to eat from every tree of the garden, except one. In contrast, Christ was in the wilderness, experiencing his humanity in its weakest condition, eating nothing. Jesus’ successful resistance of the devil while in his weakest physical state reinforces the truth of his quotation, “Man shall not live by bread alone.” His true life is sustained by “every word that proceeds out of the mouth of God.”

Dallas Willard expounds on the power that Jesus received through this time of fasting and solitude:

Dallas Willard expounds on the power that Jesus received through this time of fasting and solitude:

Jesus is consistent throughout His ministry in reminding His disciples of where true strength and power was to be found, downplaying the importance that human beings place on food, and promoting the importance of the strength and power that is found through God’s Word and Spirit:

John 4:31-34—Meanwhile the disciples were urging him, saying, “Rabbi, eat.” But he said to them, “I have food to eat that you do not know about.” So the disciples said to one another, “Has anyone brought him something to eat?” Jesus said to them, “My food is to do the will of him who sent me and to accomplish his work.

Matt. 6:25—Therefore I tell you, do not be anxious about your life, what you will eat or what you will drink, nor about your body, what you will put on. Is not life more than food, and the body more than clothing?

Jesus is expressing the same truth He spoke to Satan in the wilderness, which God, through Moses, spoke to the Israelites. It is not just physical food that sustains us; it is doing the will of God. This is the truth that underlies the practice of fasting in a Christian context. Fasting is not magic; it does not manipulate God to do our will. It is our submission to His will, as evidenced by the fact that our time is better spent in prayer or in some specific ministry than in eating a meal. Jesus subordinated eating to doing the will of God.

Fasting confirms our utter dependence upon God by finding in him a source of sustenance beyond food. Through it, we learn by experience that God’s word to us is a life substance, that it is not food (“bread”) alone that gives life, but also the words that proceed from the mouth of God. We learn that we too have meat to eat that the world does not know about (John 4:32, 34). Fasting unto the Lord is therefore understood in the Christian tradition as feasting—feasting on God’s presence and on doing his will.

The Christian poet Edna St. Vincent Millay expresses the discovery of the “other” food in her poem entitled “Feast”:

The last was like the first

I came upon no wine

So wonderful as thirst,

I gnawed at every root,

I ate of every plant,

I came upon no fruit,

So wonderful as want,

Feed the grape and the bean

To the vintner and the monger;

I will lie down lean

With my thirst and my hunger.

Upon the completion of Jesus’ time of extensive fasting in the wilderness, the Gospel writers in the three synoptic Gospels record a dialogue in which Jesus is queried as to why his disciples are not fasting. The following is from Luke 5:34-35:

The fasting query that Jesus is responding to here is derived from the covenant between God and His people in the Old Testament, in anticipation of the eschatological fulfillment of the Messiah. Jesus was that fulfillment, referred to metaphorically by Jesus as the “bridegroom,” and as such, his companions could not fast while He was still with them. The bridegroom’s presence is a cause for rejoicing and feasting—it would be a sad wedding indeed if the celebrants were expected to fast! Just how radical was the nature of Jesus’ response? Christian apologist C. S. Lewis poses a question that reveals the answer,

Yet he foresaw the era after his departure from this world when the bridegroom would be taken away, and he said this would be a time for fasting, and their fasting would be an expression of their sadness at his absence. Even so, we, as Christians, find ourselves today in an age of fulfillment since Jesus has come in fulfillment of messianic prophecy, while still being in an age of anticipation, as we await His second coming. The feast has ended, and fasting has taken its place.

There is continuity with the past in that both fasting and feasting mark the Christian’s experience. But since Christ has come, the significance of each of these practices has been reversed. Where once the faithful feasted in hope, they may now feast in realization of hope fulfilled. Where once the community fasted in mourning, they may fast because of Christ’s absence and in anticipation of His return.

As John Piper so aptly put it:

If Christian fasting is done in imitation and remembrance of Christ, then it follows that this also anticipates something. In the Gospel of Luke, an elderly prophetess named Anna, fasted and prayed in anticipation of the messiah to come. In meeting Jesus in the temple, she witnessed the fulfillment of the messianic prophecies she had earnestly awaited. (Luke 2:37). So too, Christians may now fast in anticipation of the end of the ages, longingly awaiting the new creation when all will be made right and the faithful will dwell in God’s presence for eternity. The depictions of creation’s consummation in Revelation, the final book of the New Testament, are more oriented toward feasting, signifying the end of this earthly period of mourning.

Fasting as a Spiritual Discipline

Fasting is one of the more important of the spiritual disciplines, as it is a way of practicing that self-denial required of everyone who would follow Christ (Matt. 16:24). In fasting, we learn how to suffer happily as we feast on God. One aspect of life that is certain is that we will all experience suffering at some point regardless of what else happens to us. Fifteenth century theologian Thomas a Kempis remarks: “Whosoever knows best how to suffer will keep the greatest peace. That man is conqueror of himself and the lord of the world, the friend of Christ, and heir of Heaven.”

Persons well used to fasting as a systematic practice will have a clear and constant sense of their resources in God. And that will help them endure deprivations of all kinds, even to the point of coping with them easily and cheerfully. Kempis again says: “Refrain from gluttony and thou shalt the more easily restrain all the inclinations of the flesh.” Fasting teaches temperance or self-control and therefore teaches moderation and restraint with regard to all our fundamental drives. Since food holds the pervasive place it does in our lives, the effect of fasting will be diffused throughout our personality. We discover in the midst of all our needs, wants and suffering, that we can nonetheless experience contentment. And we are told in the New Testament that “godliness with contentment, is great gain” (1 Tim. 6:6).

In the Sermon on the Mount, Christ said that his disciples should fast in secret before the Father, “and your Father who sees in secret will repay you” (Matt 6:18). Clearly this suggests that, like prayer or almsgiving, fasting with proper spiritual motives will lead to spiritual blessings from God. So while fasting may at times seem mournful, Christian fasting is also never completely separated from the anticipation of God’s Spirit breaking into our experience even now. As our attentions are lifted from sole concentration on material needs to the often unseen, world of God’s kingdom, the believer anticipates connecting with the God who can operate beyond our normal experience.

Fasting in Ministry and Service

Subsequent to Jesus’s death and resurrection, another purpose for fasting is noted in the epistles of the Apostles, which is fasting for purposes of Christian ministry, sharing of the Gospel, and service to others.

In the early beginnings of Christianity, as Jesus’ followers began to missionize and travel to new lands to share the Christian message, we read in the New Testament book of Acts that they fasted and prayed before doing so. As they appointed leaders to their fledgling churches, they also fasted and prayed. (Acts 13:2, 3; 14:23)

The True Fast

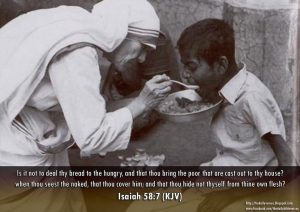

And lastly, a final purpose for fasting was for transformation that would translate into compassionate acts and service to others. For this point, I will refer to Jesus’ teaching from the Sermon on the Mount, in which He instructs His disciples as to how to fast, both physically and spiritually.

In Matthew 6:16-18 Jesus says,

Fasting for the Christian was not meant to be a public event that would enhance one’s standing in the community or the perception of a person’s spirituality or righteousness before God, but rather a time of personal reflection with the Father. When Jesus directs His followers to anoint themselves and wash their faces so that their fasting wouldn’t be seen by others, he addresses directly the issue of hypocrisy and enunciates the proper motivation for fasting. Through fasting, His followers will discover that life is so much more than food, and in turn their actions will reflect the transformative work of God in their lives.

Throughout the Sermon on the Mount, Jesus calls his disciples to a different kind and quality of righteousness than that of the religious leaders of His day. The Kingdom righteousness that Jesus is illustrating works from the inside out because it first produces changed hearts and new motivations (Rom. 6:17; 2 Cor. 5:17; Gal. 5:22–23; Phil. 2:12; Heb. 8:10), so that the actual conduct of Jesus’ followers would “[exceed] the expectations for righteousness” of his day. Thus in the Sermon on the Mount, Jesus extols the poor in spirit, those who mourn, the meek, those who hunger and thirst for righteousness, the merciful, and the peacemakers.

We need only look back to Isaiah chapter 58, to see the continuity between God’s instruction to Israel and that of Jesus’ teaching in regards to true fasting and what such fasting does in transforming the heart and actions of the individual who is exercised thereby:

Isaiah 58:6-10

to loose the bonds of wickedness,

to undo the straps of the yoke,

to let the oppressed go free,

and to break every yoke?

[7] Is it not to share your bread with the hungry

and bring the homeless poor into your house;

when you see the naked, to cover him,

and not to hide yourself from your own flesh?

[8] Then shall your light break forth like the dawn,

and your healing shall spring up speedily;

your righteousness shall go before you;

the glory of the LORD shall be your rear guard.

[9] Then you shall call, and the LORD will answer;

you shall cry, and he will say, ‘Here I am.’

If you take away the yoke from your midst,

the pointing of the finger, and speaking wickedness,

[10] if you pour yourself out for the hungry

and satisfy the desire of the afflicted,

then shall your light rise in the darkness

and your gloom be as the noonday.

In Luke 4 we find Jesus applying Isa. 61 as the foundation of His ministry and mission. It is striking how the true fast that is spoken of in Isaiah 58, is confirmed in Jesus application of what He, as the Messiah, would do in fulfilling the prophecies of His coming and ministry:

[18] “The Spirit of the Lord is upon me,

because he has anointed me

to proclaim good news to the poor.

He has sent me to proclaim liberty to the captives

and recovering of sight to the blind,

to set at liberty those who are oppressed,

[19] to proclaim the year of the Lord’s favor.”

In Matthew 25, Jesus commends the “sheep,” His followers, for their great compassion for those in need—for the hungry, the thirsty, the stranger; for those who are naked, sick, or in prison. The righteous will inherit the kingdom not because of the compassionate works that they have done but because their righteousness comes from their transformed hearts in response to Jesus’ proclamation of the kingdom, as evidenced by their compassion for the “least of these.” In caring for those in need, the righteous discover that their acts of compassion for the needy are the same as if done for Jesus himself. (Matthew 25:34-40)

In Matthew 25, Jesus commends the “sheep,” His followers, for their great compassion for those in need—for the hungry, the thirsty, the stranger; for those who are naked, sick, or in prison. The righteous will inherit the kingdom not because of the compassionate works that they have done but because their righteousness comes from their transformed hearts in response to Jesus’ proclamation of the kingdom, as evidenced by their compassion for the “least of these.” In caring for those in need, the righteous discover that their acts of compassion for the needy are the same as if done for Jesus himself. (Matthew 25:34-40)

Conclusion

In conclusion, the primary focus of Christian fasting is centered on the person and work of Jesus Christ. We as Christians live according to the ‘now, but not yet’, between the times, if you will. We fast now as our Bridegroom is not immediately with us, but we rest in the trustworthiness and assurance of the promise He has given of our being reunited with Him at the wedding feast that He is even now preparing:

“Hallelujah!

For the Lord our God

the Almighty reigns.

Let us rejoice and exult

and give him the glory,

for the marriage of the Lamb has come,

and his Bride has made herself ready;

it was granted her to clothe herself

with fine linen, bright and pure”—

for the fine linen is the righteous deeds of the saints.

And the angel said to me, “Write this: Blessed are those who are invited to the marriage supper of the Lamb.” (Revelation 19:6-9)

Until then we will continue to practice the true fast, that of “loving God with all our heart, mind, spirit and strength, and loving our neighbors as ourselves.” (Matt. 22:37-40)

Sources for this article:

Bible.org–I highly recommend their fasting page, found here

Dallas Willard, The Spirit of the Disciplines-Understanding How God Changes Lives, Harper Collins, 1998

Dallas Willard-Fasting as a spiritual discipline for renewal

Fast From Overloaded Lives-the Neglected Spiritual Discipline of Fasting

Fasting as a Spiritual Discipline