- ABOUT

- ARGUMENTS – EXISTENCE OF GOD

- The Argument from Contingency

- Cosmological Argument

- Moral Argument

- Ontological Argument

- Teleological/Design/Fine-tuning Argument

- Pascal’s Wager

- The Argument from Religious Experience

- The Argument from Miracles

- The Argument from Consciousness

- The Argument from Truth

- The Argument from Desire

- The Argument from Aesthetic Experience

- HISTORICITY – RESURRECTION

- CHRISTIANITY & ISLAM

- APOLOGETICS

ORLANDO, Fla. (NRB) – Author and Christian apologist Lee Strobel shared strategies for increasing churches’ evangelistic effectiveness during a Feb. 28 session on pastoral apologetics at Proclaim 17, the NRB International Christian Media Convention in Orlando.

Strobel, Professor of Christian Thought at Houston Baptist University and Teaching Pastor at Woodlands Church in Texas, began his presentation by saying he is concerned and fearful that the value of evangelism is diminishing in American churches. He pointed out that far too many churches are growing not so much through conversion of the lost but as by taking members from other churches. For complete article, here

Tolerance is misunderstood in America today, says a former atheist who is now a Christian apologist. Tolerance is set up by Jesus Himself in the Sermon on the Mount, in Luke 6, where Jesus talks about doing good to those who don’t necessarily do good to you, said Mary Jo Sharp director of the nonprofit apologetics ministry Confident Christianity, Inc., during The Table Podcast by Hendricks Center of Dallas Theological Seminary.

The idea of tolerance in the culture today has shifted “where we have to accept other people’s views, so there’s no possibility of doing good to those with whom we adamantly disagree,” she noted. For complete article, here

“Much of the opposition to apologetics is not from non-Christians who are offended by attempts to make Christianity seem rational, but by Christians who misunderstand the purpose of apologetics.

When I talk to atheists who say that there is no God, I ask them what kind of God do they not believe in. It may be that I don’t believe in that God either. When Christians say they don’t believe in apologetics, I would suggest asking what type of apologetics they don’t believe in.

Before suggesting that Christians should or should not embrace apologetics, it may be helpful to discuss what apologetics is and what it is not. Let’s start with what apologetics is not.”

For the complete (and excellent) article by Stephen J. Bedard, here

In a previous article, Was Paul an apostle or ‘hijacker? Let’s follow the evidence, I presented evidence from a number of scholars as to the historicity of Paul’s apostleship and the refutation of the Muslim claim of his having ‘hijacked’ the early Church. Since publishing that article, I have come across a number of articles and videos of Muslim clerics and apologists who continue to support and propagate the ‘hijacker hypothesis,’ in spite of the lack of historical and scriptural evidence for their claims. In this article I am presenting further evidence for the historical claim that Paul was indeed a true apostle, follower and teacher of the Gospel (Injeel) of Jesus Christ.

In Nabeel Qureshi’s new book, No God But One-Allah or Jesus?, he includes a chapter dealing with the Muslim claim of Paul’s alleged ‘hijacking’, offering further evidence and argument in refuting the ‘usurping deceiver’ and ‘infiltrator of the early Church,’ labels that most Muslims have placed upon the apostle Paul.

The common Muslim assertion that Paul hijacked Christianity, imposed his own teachings, and corrupted the true religion not only goes against the biblical records but also is unwarranted from a historical point of view and enjoys very little scholarly support…The problem becomes sharper when we revisit one of the Quranic verses that makes a promise to Jesus: “Indeed, I will cleanse you (Jesus) from those who disbelieve and I will make those who follow you superior to those who disbelieve, until the day of resurrection.” (3:55). Allah promises to make the disciples superior to disbelievers, and Jesus would be made free from such disbelievers. The Muslim view of Paul, that he overcome the disciples and hijacked Jesus’ message, seems to ignore the Quran’s promise to the disciples.

It would be helpful if the Quran had something to say about Paul, but it says absolutely nothing, never so much as mentioning his name. Given the pivotal role Muslims often think Paul had in corrupting Christianity, the silence is deafening. Why does the Quran not mention him? Is it on account of the Quran’s omission that Muslims in the early and classical periods of Islam, such as Tabari and Qurtubi, saw Paul as a follower of Jesus? (See Keith Thompson’s excellent article, The Historical Case for Paul’s Apostleship-And a Critique of Muslim Arguments)

In U.S. criminal law, as in other places around the world, three aspects of a crime must be established before a suspect can be found guilty: a means, a motive, and an opportunity. The Islamic view that Paul hijacked Christianity fails to secure any of these three. Paul could not have had the means because Allah promised to make the disciples insuperable: there is no viable motive for Paul to deceive the church as his efforts earned him only persecution and a death sentence; and there is no model suggested that clarifies how Paul might have had an opportunity to overcome all the disciples and hijack the church. Of course, not only should Paul be considered innocent until proven guilty, but as far as this investigation is concerned, there simply is no evidence to convict him. Case closed.[1]

In his chapter, God’s Greatness and the Preservation of the Gospel, Abdu Murray offers further insight into the Muslim claims regarding the apostle Paul:

Every argument I had once used to convince Christians that the Bible had been corrupted was being dismantled one by one-by the very sources I relied on as a Muslim. (See article, Is the Bible textually corrupt? Muslims say yes, the Qur’an says no!, here) As I discovered this kind of information, the common Muslim belief that Paul hijacked Christianity in its early stages no longer made any sense. The Qur’an specifically says in two places that Jesus and his followers were not defeated by those who sought to corrupt God’s message.

Behold! Allah said: “O Jesus! I will take thee and raise thee to Myself and clear thee (of the falsehoods) of those who blaspheme; I will make those who follow thee superior to those who reject faith, to the Day of Resurrection: Then shall ye all return unto Me, and I will judge between you and the matters wherein ye dispute.” (Sura 3:55, emphasis mine)

O ye who believe! Be ye helpers of Allah: as said Jesus the son of Mary to the Disciples, “Who will be my helpers to (the word of) Allah?” Said the Disciples, “We are Allah’s helpers!” Then a portion of the Children of Israel believed, and a portion disbelieved: But We gave power to those who believed against their enemies, and they become the ones that prevailed. (Sura 61:14, emphasis mine)

Well-known Muslim commentator Al-Qurtubi says that Sura 61:14’s reference to the disciples included Paul:

It was said that this verse was revealed about the apostles of Jesus, may peace and blessing be upon him. Ibn Ishaq stated that of the apostles and disciples that Jesus sent (to preach) there were Peter and Paul who went to Rome…Allah supported them (the apostles) with evidence so that they prevailed, meaning they became the party with the upper hand.

If a Muslim is to take these verses seriously, he simply cannot believe that someone like Paul came along in the earliest days following Jesus’ ministry and completely took it over, corrupting Jesus’ original message while the disciples were still alive to oppose him. if that had happened, in what sense could Jesus’ disciples have been granted victory to the “Day of Resurrection”? If Paul had hijacked Jesus’ message, would this not have made Jesus and his disciples abject failures? To suggest such a thing flies directly in the face of the Qur’anic text and Muslim beliefs that Jesus was a great prophet. The New Testament text leaves no real room for this argument either. For Paul to have been the founder of Christianity by hijacking Jesus’ message, we would have to see evidence in Paul’s writings that he was uninterested in Jesus’ life and teachings and that he espoused teachings inconsistent with Jesus’ core teaching. But we see nothing of the kind. In fact, we find that Paul was interested in Jesus’ life, referring to specific events recorded in the Gospels.

If a Muslim is to take these verses seriously, he simply cannot believe that someone like Paul came along in the earliest days following Jesus’ ministry and completely took it over, corrupting Jesus’ original message while the disciples were still alive to oppose him. if that had happened, in what sense could Jesus’ disciples have been granted victory to the “Day of Resurrection”? If Paul had hijacked Jesus’ message, would this not have made Jesus and his disciples abject failures? To suggest such a thing flies directly in the face of the Qur’anic text and Muslim beliefs that Jesus was a great prophet. The New Testament text leaves no real room for this argument either. For Paul to have been the founder of Christianity by hijacking Jesus’ message, we would have to see evidence in Paul’s writings that he was uninterested in Jesus’ life and teachings and that he espoused teachings inconsistent with Jesus’ core teaching. But we see nothing of the kind. In fact, we find that Paul was interested in Jesus’ life, referring to specific events recorded in the Gospels.

In Colossians 3:13, Paul makes a reference to Jesus’ teaching in the Lord’s Prayer that we are forgiven as we forgive (see Mark 11:25). In Galatians 5:13-14, Paul practically quotes Jesus’ teaching that loving our neighbor as we love ourselves fulfills the entire law (see Matthew 22:38-40). Paul specifically mentions several facts in Jesus’ life, including the Last Supper, in which Jesus broke bread and drank wine to show the symbols of the new covenant (compare 1 Corinthians 11:23-26; Matthew 26:26-29).

Neither the text of the Bible nor the text of the Qur’an nor the early Muslim commentaries support the view that Paul hijacked Christianity. As N. T. Wright noted during his debate on that very subject with (now former) atheist A. N. Wilson, “Paul was one true voice in a rich harmony of true voices of the early church, but the writer of the song was Jesus.”[2]

Qur’an Affirms Paul As a Messenger of God-Infinity Apologetics Clips

Did the Apostle Paul Invent Christianity?-Jay Smith-One Minute Apologist

The Historical Case for Paul: A Critique of Muslim Arguments

More resources on the topic:

Did Paul Invent Christianity? Is the Founder of the Christian Religion Paul of Tarsus or Jesus of Nazareth?-by Rich Deem, here

What about Paul? Responses to Muslim claims of Paul corrupting the Gospel of Jesus-found, here

References

[1] Nabeel Qureshi, No God But One-Allah or Jesus?, Zondervan, 2016, pgs. 205-206

[2] Abdu Murray, Grand Central Question-Answering the Critical Concerns of the Major Worldviews, Intervarsity Press, 2014, pgs. 184-85

To my Muslim friends, as-salāmu ‘alaykum! Having spent a great deal of time in conversation with you in regards to the nature of God and the differences found in the two concepts, Trinity and Tawhid, I wanted to offer the following explanations, arguments and Scriptural foundation for the triune nature of God. I realize that a number of you may have heard the following explanations and arguments for the Trinitarian God, but I would venture to say that many of you have not. It is for this reason that I have compiled the following testimonies, articles and videos for you to peruse. It is my hope that the following material will provide you with an accurate explanation of what we, as Christians, believe and are saying when we speak of the Trinity and the Triune God. I look forward to further conversations on the topic. As God told the prophet Isaiah, “Come now, let us reason together…” (Isaiah 1:18)

I will begin with the writings of Abdu Murray. Abdu is a lawyer and former Shia Muslim. He converted to Christianity after thoroughly investigating the truth claims of the Christian faith. The following are excerpts of his explanation and defense of the Trinitarian God:

I have come to the conclusion that Islam’s rejection of the Trinity is one of the most profound ironies in comparative religion. Islam rejects the Trinity out of a fear that it leads to the unforgivable sin of shirk, which is saying that God has partners. Shirk is Islam’s cardinal sin because it diminishes God’s greatness by saying that he is equaled by another or that he needs associates to do what he wants or to be who he is. The irony is that, when properly understood, the Trinity is the very doctrine that glorifies God as the self-subsisting, coherent yet completely transcendent being that Muslims claim him to be.

For those Muslims who see what the Bible teaches, the Trinity puts them in a difficult position. To reject the Trinity, a Muslim may resort to claiming that it is a corruption of the Bible, but he cannot do so, because the Qur’an does not allow Muslims to believe in biblical corruption. (See my article addressing biblical corruption, here) So Muslims who truly understand this tension are left with only one avenue: they must reinterpret the Bible so that it does not teach the Trinity…Muslims do not need to resort to such measures if their sincere goal is to believe in the one and only great God. If it is, then I would argue that they must believe in the Trinity for three reasons. First, the Bible (which a Muslim must believe is uncorrupted) teaches it. Second, the Trinity does not defy logic. And third, the Trinity proves God to be the Greatest Possible Being over and above a Unitarian conception of God.

…Muslims ultimately do not have to sacrifice their sense of reason to see the reality of the Trinity. They can embrace the truth because it is taught in the Scripture, because it is consistent with logic and because it transcends human logic. This is a key distinction that must be kept in mind. A truth, like the Trinity, can exceed our logic without violating it. A concept can be transcendent in the sense that it is not illogical-it is not contradictory-but it is beyond our ability to full understand. Muslims and Christians share many such beliefs. They believe that God is a being without beginning and without end. There is nothing inherently contradictory about the belief in God’s eternality, yet it is impossible for us to understand fully. How can we? We are finite beings, each of us with a beginning, living in a world where everything in the natural order has a beginning. So it would be impossible to comprehend God’s eternality fully, though we might be able to apprehend it.

The Trinity is not the belief that God is one in his nature and three in his nature. That would be an obvious breach of the law of noncontradiction. Similarly, the Trinity is not the belief that God is one in his personhood and three in his personhood. That, Too, is explicitly contradictory and nonsensical. In distinction to either of these ideas, the Trinity is the belief that God has one nature-one essence-and three personhoods, or three centers of consciousness. This would be contradictory only if something’s “nature” is the same as its “person,” because then the Trinity would teach that God is only one in one sense and also three in the same sense. But “nature” and “person” are distinct concepts, which keeps the Trinity from internal inconsistency. Perhaps an illustration will help us unpack the nature/person distinction. Something’s nature is its very basic or inherent characteristic. A nature is what some is. One can look at a rock and ask what it is. In its most basic nature, a rock is a nonliving or inorganic thing. But “personhood” is a far different thing. Personhood describes something’s relational, volitional, intellectual and emotional qualities. Human beings have personhood because they relate to one another and to the world around them. They have a will an intellect and emotions. But a human being also has a nature, a basic or inherent characteristic.

And so we see that nature and personhood are distinct concepts. And as distinct concepts, there is no law of logic that is violated-there is no contradiction-in claiming that God is one in his nature and three in his personhoods. This may transcend our reason, but it does not defy it. Just because we cannot fully comprehend how a single being can be tri-personal does not mean it is not possible…Muslims’ affirmation of God’s differentness practically screams out for the answer found in the Trinity. In fact, I would expect a Muslim to readily acknowledge that if God in his very nature were simple to understand because he resembles our single nature/single person existence, perhaps we invented him to be that way. In other words, if God in his very being looks just like us, then the chances are quite good that we created him our image instead of the other way around. A Muslim would perish the thought. And so rather then bother us, the Trinity’s grand yet logically consistent mystery provides us with solace that we are on to something marvelous to our pursuit to worship the Greatest Possible Being.[1]

Another proof given for the triune nature of God, is that of unity in diversity, which is grounded in love. Augustine of Hippo saw love as the best explanation of the nature of the Trinity. “Now when I, who am asking about this, love anything, there are three things present: I myself, what I love, and love itself. For I cannot love love unless I love a lover; for there is no love where nothing is loved. So there are three things: the lover, the loved and the love.”[3] From this analogy, Augustine argues that God’s nature is indeed relational and personal as it is expressed in a divine community of love. It cannot be said that God is love (1 John 4:8) if God is alone and monadic. Instead, love resides both in God’s nature as a personal being and in relationship to the beloved (Jesus Christ) by love (Holy Spirit). Christian philosophers, J. P. Moreland and William Lane Craig, offer the following treatise on the Trinity which echos back to Augustine’s analogy:

We close with an argument that a number of Christian philosophers have defended for God’s being a plurality of persons:

- God is by definition the greatest conceivable being.

- As the greatest conceivable being, God must be perfect.

- Now a perfect being must be a loving being. For love is a moral perfection; it is better for a person to be loving rather than unloving. God therefore must be a perfectly loving being.

- Now it is of the very nature of love to give oneself away. Love reaches out to another person rather than centering wholly in oneself. So if God is perfectly loving by his very nature, he must be giving himself in love to another.

- But who is that other? It cannot be any created person, since creation is a result of God’s free will, not a result of his nature. It belongs to God’s very essence to love, but it does not belong to his essence to create. So we can imagine a possible world in which God is perfectly loving and yet no created persons exist. So created persons cannot sufficiently explain whom God loves.

- Moreover, contemporary cosmology makes it plausible that created persons have not always existed. But God is eternally loving. So again created persons alone are insufficient to account for God’s being perfectly loving.

- It therefore follows that the other to whom God’s love is necessarily directed must be internal to God himself. In other words, God is not a single, isolated person, as unitarian forms of theism like Islam hold; rather, God is a plurality of persons, as the Christian doctrine of the Trinity affirms. On the unitarian view God is a person who does not give himself away essentially in love for another; he is focused essentially only on himself. Hence, he cannot be the most perfect being.

- But on the Christian view, God is a triad of persons in eternal, self-giving love relationships. Thus,

- Since God is essentially loving, the doctrine of the Trinity is more plausible than any unitarian doctrine of God. (emphasis mine)[2]

Thank you my friends for considering the above explanations of the Trinity. I hope they are helpful in furthering your understanding of what we, as Christians, truly believe God to be, both in essence and personhood. (For more on Trinty and Tawhid, here) If you have questions, or would like to discuss the Trinity and Tawhid further, please feel to contact me at: 4Lane.davis@gmail.com

Until then, Ma’a al-salaama!

Is the Trinity a contradiction?-Abdu Murray-Q&A RZIM

Nabeel Qureshi (former Muslim) explaining the Trinity

Is The Trinity Unscriptural And Unreasonable?-Brett Kunkle-str.org

Logical Defense of the Trinity-William Lane Craig

References

[1] Abud Murray, Grand Central Question-Answering the Critical Concerns of the Major Worldviews, Intervarsity Press, 2014, pgs. 190, 196-197, 200

[2] J. P. Moreland & William Lane Craig, Philosophical Foundations for a Christian Worldview, Intervarsity Press, 2003, pgs. 594-5

Is Islam a religion of peace?

This year’s Understanding and Answering Islam (UAI) is designed to pick up on the issue of peace and what it means, especially in regard to Islam. Secularists are very public and vocal about the claim that religions are the source and reason for much of the violence in the world and if we could just end religious influence and teaching, the world would be a better and safer place. At first glance they seem to have good reasons behind their claims: since last year’s UAI, from Brussels to Orlando to Aleppo, from shopping malls to transportation hubs, from individuals to Islamic State, numerous acts of religious terror have dominated news headlines and social media.

Many spokespersons for and on behalf of Islam are quick to say Islam is a religion of peace. Many of us have spoken to ordinary Muslims who firmly believe that any violence perpetrated in the name of Islam is a corruption of their faith. At the same time, critics of Islam are just as quick to respond that Islam is inherently violent since this is exemplified, and even commanded, in its authoritative texts. These critics claim that the violence we see today is not an aberration, but the continuance of a pattern seen throughout Muslim history. Which is more accurate? Our expert speakers, including those from Muslim backgrounds, will speak to the issue of peace, especially in regard to Islam’s central doctrines, its theological debates, its history and the everyday experience and aspirations of Muslims.

Christians also claim they follow a religion of peace, indeed that Jesus is the “Prince of Peace.” Proclaiming this in the public square presents Christians with a perplexing and complex set of challenges. We are uncomfortably taken to task publicly for the violence in the Old Testament and for many of the historic examples of things done in the name of Christianity. In the encounter with Islam, in particular, the Crusades loom as a major apologetic challenge. How can Christians challenge Muslims about peace without risk of hypocrisy? Our speakers will seek to equip Christians to speak powerfully, and graciously, into this debate with a true gospel of peace that successfully negotiates these objections.

In the current social, global-political, and religious climate, few issues are more pressing for Christians than to properly engage Islam on the question of peace. To that end, we hope you and your friends, families, and church communities will join us for this year’s Understanding and Answering Islam. As we journey together in an environment of prayerful dependence on God, our global speaking team will equip you with the depth of understanding that is needed to thoughtfully invite your family members, friends, neighbors, and co-workers into the kingdom of God’s peace.

Conference web site and registration, here

In a recent article, Relativism and the Redefining of Tolerance, I highlighted both relativism and its impact on and redefining of the definition and concept of tolerance. In this brief article, I want to highlight the findings of a recent Barna survey, The End of Absolutes: America’s New Moral Code, which shows how over the last 60 years relativism, along with its cohorts–scientism, material naturalism, humanism, and hedonism–have formed a new moral code for the majority of its populace:

In a recent article, Relativism and the Redefining of Tolerance, I highlighted both relativism and its impact on and redefining of the definition and concept of tolerance. In this brief article, I want to highlight the findings of a recent Barna survey, The End of Absolutes: America’s New Moral Code, which shows how over the last 60 years relativism, along with its cohorts–scientism, material naturalism, humanism, and hedonism–have formed a new moral code for the majority of its populace:

Two-thirds of American adults either believe moral truth is relative to circumstances (44%) or have not given it much thought (21%). About one-third, on the other hand, believes moral truth is absolute (35%). Millennials are more likely than other age cohorts to say moral truth is relative—in fact, half of them say so (51%), compared to 44 percent of Gen-Xers, 41 percent of Boomers and 39 percent of Elders. Among the generations, Boomers are most likely to say moral truth is absolute (42%), while Elders are more likely than other age groups to admit they have never thought about it (28%).

Using the statistics above, let’s break down the progression of relativism and the breakdown of moral absolutes within the U.S. (and Western society in general) over the last 60 years. In response to the statement, ‘moral truth is relative,’ this poll indicated a steady increase in the affirmative for a relativistic worldview:

Elders-those born before or during World War II-1920-1945-39%

Boomers-born during the post–World War II baby boom, approximately between the years 1946 and 1964-41%

Gen-Xers-born in the 1960s and 1970s-44%

Millennials-a person reaching young adulthood around the year 2000-51%

Boomers-born during the post–World War II baby boom, approximately between the years 1946 and 1964-41%

Gen-Xers-born in the 1960s and 1970s-44%

Millennials-a person reaching young adulthood around the year 2000-51%

I found the first sentence to be illuminating, “Two-thirds of American adults either believe moral truth is relative to circumstances (44%) or have not given it much thought (21%)“. If one-fifth of the population has fallen into such an apathetic state of non-reflection and unconcern in regards to where morality fits within their worldview, not to mention that of their society/culture, it is not surprising that relativism has steadily overtaken an objective moral worldview such as is found in Christianity.

However, the fact is that almost no one is that apathetic when confronted with the serious questions of objective moral values, as philosopher Paul Copan illustrates:

Moral relativism is intuitively implausible. And when we are willing to ask serious questions about morality, we find that we don’t really believe that moral values are relative. Just ask yourself: “Do you right now believe that it’s okay to murder or to be murdered?” You might think: “Well, some people have thought so.” But the question is: “Do you–not other people–right now have any doubt about the wrongness of murder?” This is the place to begin–not what other people have alleged. So we don’t have to waste our time talking about what we both accept as true. We can, instead, begin discussing the real issue–namely, which viewpoint best accounts for the existence of objective moral values.[1]

The apostle Paul gave the following exposé of relativism (i.e. rejection of objective moral truth claims) 2,000 years ago:

For the wrath of God is revealed from heaven against all ungodliness and unrighteousness of men, who by their unrighteousness suppress the truth. For what can be known about God is plain to them, because God has shown it to them. For his invisible attributes, namely, his eternal power and divine nature, have been clearly perceived, ever since the creation of the world, in the things that have been made. So they are without excuse. For although they knew God, they did not honor him as God or give thanks to him, but they became futile in their thinking, and their foolish hearts were darkened. Claiming to be wise, they became fools, and exchanged the glory of the immortal God for images resembling mortal man…taken captive by philosophy and empty deceit, according to human tradition, according to the elemental spirits of the world, and not according to Christ. (Romans 1:18-23; Colossians 2:8 ESV)

The suppression of truth which Paul refers too, has been alive and thriving throughout the past millenia, ever since the author of relativism, Satan, presented his relativistic ideology to Eve: “did God actually say?” (Gen. 3:1) Paul not only exposes the relativistic ideology, but the reason for it: “For although they knew God, they did not honor him as God or give thanks to him, but they became futile in their thinking, and their foolish hearts were darkened.” When a person, or a society/culture becomes disconnected from God, who is the source of all moral goodness, the alternative of choice in Western countries has proved to be: relativism.

The suppression of truth which Paul refers too, has been alive and thriving throughout the past millenia, ever since the author of relativism, Satan, presented his relativistic ideology to Eve: “did God actually say?” (Gen. 3:1) Paul not only exposes the relativistic ideology, but the reason for it: “For although they knew God, they did not honor him as God or give thanks to him, but they became futile in their thinking, and their foolish hearts were darkened.” When a person, or a society/culture becomes disconnected from God, who is the source of all moral goodness, the alternative of choice in Western countries has proved to be: relativism.

Some may object to the claim that God is the source of all moral goodness and that objective moral values are rooted in His very nature. However, when one compares the theistic worldview with that of the naturalistic worldview, it soon becomes clear that the theistic worldview is not only more plausible, but it also makes better sense of the world in which we live. Again, Paul Copan offers the following analogy on the topic:

If God existed, we would certainly expect objective moral values to exist. Such values would not be surprising or unnatural at all. After all, if we humans have been made to resemble God in certain important respects, if we have been created in the “image” of a personal, good God (as traditional theism affirms), then we should not wonder that each of us has intrinsic dignity and worth, that we are morally responsible agents, that we have the capacity to recognize moral truths, and that we have certain moral obligations. It should, further, be noted that morality relates only to persons–not to rocks or non-personal entities like ants, rats, or chimps, which are not morally responsible and have no moral obligation. But if God does not exist, then we can rightly ask: “How does objective morality emerge from non-moral processes? If God does not exist, on what basis should I think that I have intrinsic dignity and worth? How does one account for this emergence of dignity if nature is all there is? If there are moral laws to the universe, then why think that they have to do only with us humans and not other living organisms?”

Of course, people can be atheists or non-theists (i.e., who do not believe in a personal God) and still share the same moral values as theists (who believe in a personal God). Furthermore, they can develop moral systems which assert the same kinds of values that the theist affirms. This is not surprising since atheists too have been made in the image of a good God–even though they do not acknowledge this. So the issue to face is not, “Do I recognize certain moral values to be objectively true?” Rather, it is, “If I recognize these moral values to be true, which viewpoint offers the best foundation for these moral values? Is it the viewpoint which presupposes an impersonal, non-moral, unguided series of steps in a long naturalistic process? Or is it a viewpoint which presupposes a personal, good Creator and Designer, who has made us to relate personally to him and to live our lives according to the pattern which reflects his moral character (theism)? It seems clear that theism, which is supernaturalistic (there is a reality beyond nature), offers a more plausible picture for affirming these values than does a naturalistic one. So we have seen that moral relativism is rationally indefensible and practically unlivable. Furthermore, if we do affirm objective moral values and intrinsic human dignity, a theistic context helps us make better sense of these moral facts than does an atheistic or non-theistic one.[2]

It is our duty as Christians to equip ourselves as Christian case-makers so we are prepared to confront relativism (the decline of objective moral values) via presenting these serious questions in conversations with our friends, family, colleagues, acquaintances. In doing so we will be ‘flipping the switch’ within their unreflective minds and helping to wake them up to the need of seriously considering their stance on objective moral values, as well as a number of other unsubstantiated stances/positions they may be holding to within their worldview. Remember, every worldview has to answer four questions: 1) What are our origins? 2) What is the purpose and meaning of life-why am I here? 3) Morality-how do we decide as to what is right and what is wrong; how do we differentiate between what is good and what is evil? 4) Ultimate destiny-when I die, what is my destination? These are the questions that we, as Christians, need to be asking of those the Lord brings across our path.

I invite you to take an insightful and instructive journey on the topic via the following videos. I believe you will be strengthened in your convictions in proclaiming “the Way, the Truth and the Life,” (John 14:6) to those who are awash in the sea of relativism of our age.

Are Morals the Result of Social Conditioning?-William Lane Craig

What’s The Best Explanation For Moral Laws?-J. Warner Wallace

Where do Objective Morals Originate in the Universe?-William Lane Craig

What is Moral Relativism-Steven Garofalo-One Minute Apologist

If you are committed to working on becoming equipped as a Christian case-maker, I highly recommend Greg Koukl’s books, Tactics-A Game Plan for Discussing Your Christian Convictions, and The Story of Reality-How the world began, how it ends, and everything important that happens in between.

See also the following related articles:

True for you, but not for me…but can that be true?, here

Christian Theism & Material Naturalism-can they both be true?, here

References:

[1] Paul Copan, Is Everything Really Relative?-Examining the Assumptions of Relativism and the Culture of Truth Decay, Published by RZIM, 1999, pg. 33-34

[2] Ibid, pg.35-36

Clive Staples Lewis is an author celebrated and beloved the world over, remembered not only for his meaningful fiction, but for the strength of his written work in Christian apologetics.

His work wells up from the deep roots of his faith, and flows forth from an imagination that took that faith and transformed it into stories and wisdom.

But from where did the distinctly Christian imagination of C.S. Lewis come? There lies a clue in a line Lewis’s book, “Surprised by Joy”.

“A young man who wishes to remain a sound Atheist cannot be too careful of his reading.”

When he wrote this sentence, Lewis was thinking of one man—George Macdonald.

Born 1824, MacDonald was a Scottish minister, author, and poet. He was also a pioneer of fantasy literature, and a major influence on such writers as J.R.R. Tolkien, Walter de la Mare, and Madeleine L’Engle.

But he influenced none, perhaps, as much as he did Lewis, who came to consider MacDonald his literary and spiritual mentor. Complete article, here

I recently attended the Evangelical Theological Society conference held in San Antonio, Texas (2016). The theme of the conference was, The Trinity. As I work in the evangelistic area of ministry to Muslims, I focused my time on the conference sessions that were devoted to on Christian-Muslim dialogue and theology. One of the sessions was entitled, Do Christians and Muslims Worship the Same God? As many of you know, this has become a hot button topic since the dispute at Wheaton College involving Professor Larycia Hawkins, in the latter part of 2015. (For more on this topic, article here.)

Dr. Imad Shehadeh, in his paper, Allah and the Trinity[1], offers the following insight and perspective on the question, ‘do Christians and Muslims worship the same God’:

(We begin in the paper with a quote from Duane Litfin): “The question of whether Muslims and Christians worship the same God “is not only unhelpful but perhaps worse than unhelpful. The question appears incapable of generating a satisfactory answer, and when well-intentioned people try to answer it anyway, as they often do, the typical result is turmoil and confusion. How could it be otherwise? Any question that can only be answered with a ‘Maybe, maybe not…is doomed from the outset… How much ‘sameness’ is required to answer yes? How much difference to answer no?”[2]

The solution to this stalemate is that the question that should be asked is not about sameness, but about difference. What is the belief that Christianity has that Islam does not adhere to? From this difference stems all other differences.

Again, Litfin is helpful here,

“Understanding what Islam and Christianity do and do not hold in common is an important task these days, but asking whether Muslims and Christians worship the same God will not get us there. If our goal is to compare these two religions we need to shift our focus to a much more illuminating question: How do Christianity and Islam differ?”

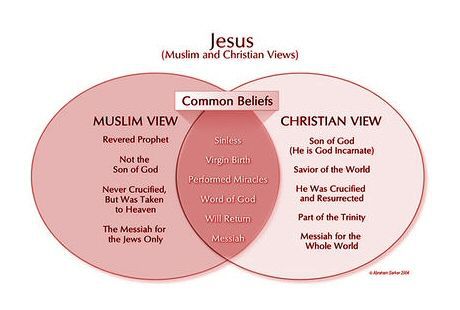

There is an unavoidable difference in the conception of God as spoken of by Christianity and Islam. This difference is in one word: the gospel. Both have common beliefs, but Christianity goes much further than Islam does, holding to core beliefs about God not found in Islam and even strongly rejected by it.[3]

In his book, Is the Father of Jesus the God of Muhammad?, Dr. Timothy George addresses the question, ‘do Christians and Muslims worship the same God.’ He states:

Is the Father of Jesus the God of Muhammad? The answer to this question is surely both yes and no. Yes, in the sense that the Father of Jesus is the only God there is. He is the sovereign Creator and Judge of Muhammad, Confucius, Buddha—indeed, of every person who has ever lived, except Jesus, the one through whom God made the world and will one day judge it (Acts 17:31; Col. 1:16). The Father of Jesus is the one before whom all shall one day bow the head and bend the knee. (Phil. 2:5-11). It is also true that Christians and Muslims can together affirm many important truths about this great God—his oneness, eternity, power, majesty. As the Quran puts it, God is “the Living, the Everlasting, the All-High, the All-Glorious” (2:256)

But the answer to the question “Is the Father of Jesus the God of Muhammad?” is also no, for Muslim theology rejects the fatherhood of God, the deity of Jesus Christ, and the personhood of the Holy Spirit—each of which is an essential component of the Christian understanding of God. No devout Muslim can call the God of Muhammad “father,” for this, in Islamic thought, would compromise divine transcendence. But no faithful Christian refuse to confess with joy and confidence, “I believe in God the Father, Almighty!” Apart from the revelation of the Trinity and the Incarnation, it is possible to know that God is, but not who God is.[4]

But the answer to the question “Is the Father of Jesus the God of Muhammad?” is also no, for Muslim theology rejects the fatherhood of God, the deity of Jesus Christ, and the personhood of the Holy Spirit—each of which is an essential component of the Christian understanding of God. No devout Muslim can call the God of Muhammad “father,” for this, in Islamic thought, would compromise divine transcendence. But no faithful Christian refuse to confess with joy and confidence, “I believe in God the Father, Almighty!” Apart from the revelation of the Trinity and the Incarnation, it is possible to know that God is, but not who God is.[4]

Carl F. H. Henry offers further insight:

In the post-Christian area, Muhammad gave fresh impetus to the lost abstract monotheism of the non-Hebrew world. To be sure, his emphasis that there is no God but Allah leans heavily on the Mosaic revelation. But an obscure doctrine of revelation crowds out the living monotheism of the Old Testament and allows Muhammad to emerge as Allah’s prophet; moreover it clouds the dynamic monotheism of the New Testament by displacing the revelation of the supremacy and deity of Jesus Christ.”[5]

In his paper, Allah and the Trinity, Dr. Imad Shehadeh explains how Islam’s changing of concepts, predicates and attributes pertaining to the God of both the Old and New Testament, results in the “speaking of a different subject all together.

The starting for both Christianity and Islam is belief in both the existence of God and the oneness of God. However, Christianity and Islam proceeded in two different directions. This resulted in a vast difference of opinion in regard to the question of whether they believe in the same God or not. To put it another way, is the starting point the same?

Both Christianity and Islam believe in the existence and oneness of God, but this belief is so fundamental and rudimentary that even the fallen angels believe the same. The Bible challenges the person that has this faith saying, “You believe that God is one. You do well; the demons also believe, and shudder” (James 2:19).

Islam later presented a different concept of the same word “Allah” used beforehand by Jews and Christians. The result was that there ends up being a similar subject with different predicates, or attributes. This different concept made it impossible for Islam to move in the same direction that Christianity was moving on, with its foundation in the Old Testament of the Bible, and continuing into the New Testament.

From the beginning, the Old Testament laid the foundation for a unique concept of the unity of God that required explanation. This explanation came later in the New Testament. The New Testament declared a complete and unique concept of the unity of God, which is Relational Oneness. The Quran and Hadith declare a completely different concept, and it is Absolute Oneness. As Mombasa put it over a century ago, “the adoption of the faith of Islam by the pagan people is in no sense whatever a stepping-stone towards, or a preparation for, Christianity, but exactly the reverse.”

The concept of God in his predicates or attributes in Islam become so different that they redefine the subject! This then reintroduces the starting point in Islam and Christianity as having different subjects all together. It is then easy to conclude that Islam seems to start with the same subject, but it later demonstrates that it is actually speaking of a different subject altogether! As Carl Henry asserted, “The importance of the discussion of divine attributes is apparent from the fact that one often alters a subject by applying different predicates to it.”[6]

John Paul ll offers the following commentary in regards to the distance between Islam and Christianity, both theological and anthropological:

“Whoever knows the Old and New Testaments, and then reads the Qur’an, clearly sees the process by which it completely reduces Divine Revelation. It is impossible not to note the movement away from what God said about Himself. First in the Old Testament through the prophets, and then finally in the New Testament through His Son. In Islam all the richness of God’s self-revelation, which constitutes the heritage of the Old and New Testaments, has definitely been set aside.

Some of the most beautiful names in the human language are given to the God of the Quran, but He is ultimately a God outside of the world, a God who is only Majesty, never Emmanuel, God-with-us. Islam is not a religion of redemption. There is no room for the Cross and the Resurrection. Jesus is mentioned, but only as a prophet who prepares for the last prophet, Muhammad. There is also mention of Mary, His Virgin Mother, but the tragedy of redemption is completely absent. For this reason not only the theology but also the anthropology of Islam is very distant from Christianity.”[4]

Abdu Murray, a former Shia Muslim who converted to Christianity, offers the following perspective in regards to his experience on ‘both sides of the same God fence,’ so to speak. He said:

When I became a Christian, I didn’t suddenly say, “I believe in God now,” like I was an atheist before or something. That’s not how I thought of it. I just thought to myself, “Oh I believe in God correctly now, or I believe the true things about God.” Because there are differences. The fundamental difference is God’s oneness. Now, Muslims and Christians agree on something, there is one God. Christians call him Yahweh and Muslims call him Allah, but there is only one. But Muslims say that God is one in his nature and one in his person, he’s an undifferentiated absolute, what is called a monad concept of God. Whereas Christians are Trinitarians, we believe that God is one in his nature and three in his personhoods. Now that’s significant because you can’t have a completely great self-sufficient being without a Trinitarian being. Also, the Trinity makes sense of the Incarnation, it also makes sense of the atonement, because the Son is paying something to the Father and they have to be distinct in some sense, there has to be a real actual transaction…God in Islam is not Trinitarian, in fact that is considered blasphemy in Islam…Prominent Muslim and Islamic scholar, Al-Faruqi has stated, “This is the deepest difference between Islam and Christianity, the knowability of God.” [In Islam] He’s not a person to be known, he is a will to be followed.”[8]

At first blush, it may seem that Abdu’s testimony supports the, ‘Christians and Muslims worship the same God, but the Muslims simply worship him imperfectly and/or incorrectly.’ But when taking his testimony in the context as to who Christians and Muslims identify and believe Yahweh and Allah to be, it becomes clear that they do not worship the same God. As is stated above, simply believing in the oneness of a creator God is not the same as believing in a Creator God who is personal, Triune and has acted and entered into His creation to bring salvation to each human being who chooses to receive His marvelous gift. Again, referring to Dr. Imad Shehadeh analysis above, “The concept of God in his predicates or attributes in Islam become so different that they redefine the subject! This then reintroduces the starting point in Islam and Christianity as having different subjects all together. It is then easy to conclude that Islam seems to start with the same subject, but it later demonstrates that it is actually speaking of a different subject all together!”

Scottish Anglican scholar Stephen Neill, states what I consider the core issue posed by the question, ‘Do Christians and Muslims worship the same God?’:

“Christians and Muslims alike passionately proclaim belief in one God. But everything depends on the meaning we put into the word “God.”

References:

[1] Dr. Imad Shehadeh, Allah and the Trinity, presented at the Evangelical Theological Society Conference, 2016

[2] Duane Litfin, The Real Thological Issue Between Christnas and Muslims, Christianity Today, 2016

[3] Ibid

[4] Timothy George, Is the Father of Jesus the God of Muhammad?, Zondervan, 2002, pgs. 69-70

[5] Carl F. H. Henry, God, Revelation and Authority, Waco, Tx., Word, 1982, pg. 171

[6] Dr. Imad Shehadeh, Allah and the Trinity, presented at the Evangelical Theological Society Conference, 2016

[7] John Paul ll, Crossing the Threshold of Hope, Jonathan Cape Ltd; Unabridged edition, 1994

[8] Abdu Murray, Is the God of Islam the same as the God of the Bible?, Interview with Reasons to Believe, here I highly recommend Abdu Murray’s book: Grand Central Question-Answering the Critical Concerns of the Major Worldviews

Do Christians and Muslims Worship the Same God?-William Lane Craig-reasonablefaith.org

Is the Father of Jesus the God of Muhammad?-Timothy George

Do Muslims and Christians Worship the Same God?-Alan Shlemon-str.org

Is the God of Islam the same as the God of the Bible?-Abdu Murray

For further study on the topic:

Do Christians and Muslims Worship the Same God?-William Lane Craig, here

Do Muslims and Christians Worship the Same God?-Debate-Prof. Miroslav Volf vs. Nabeel Qureshi, here

Is faith based on evidence, or is it trusting in something you cannot see? Can it be both?

Today marks the feast day of St Catherine of Alexandria, who is regarded by Catholic tradition as the patron saint of apologists. Legend says that Catherine was born in Alexandria, Egypt, a sophisticated hub of culture and learning. Her noble birth granted her an excellent education and she was a gifted scholar. A vision at a young age brought her to Christianity, so when the Emperor Maxentius began persecuting Christians, the teenage scholar denounced his actions.

Instead of having her executed, Maxentius ordered 50 orators and philosophers to debate Catherine. The story says however that Catherine, moved by the power of the Holy Spirit, spoke with eloquence in defence of the faith. So convincing were her words that many of the pagans were themselves converted in response. Catherine could be neither defeated in argument, nor forced to give up her beliefs. Legend even states that Maxentius’s own wife was converted, before Catherine was eventually put to death.

We don’t know exactly how much of this story is true, or if Catherine really existed, but she remains a prominent and important saint in Church tradition. St Catherine’s story teaches us about the power of an apologia (a defence or explanation) for the faith, using reason and rhetoric to point to the truth of Christianity. Complete article, here